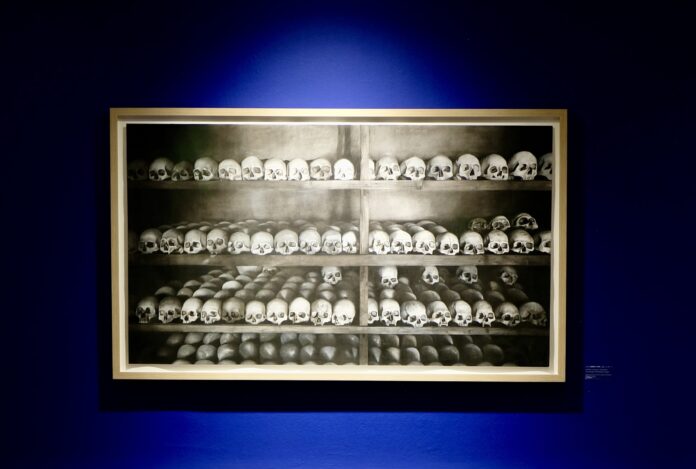

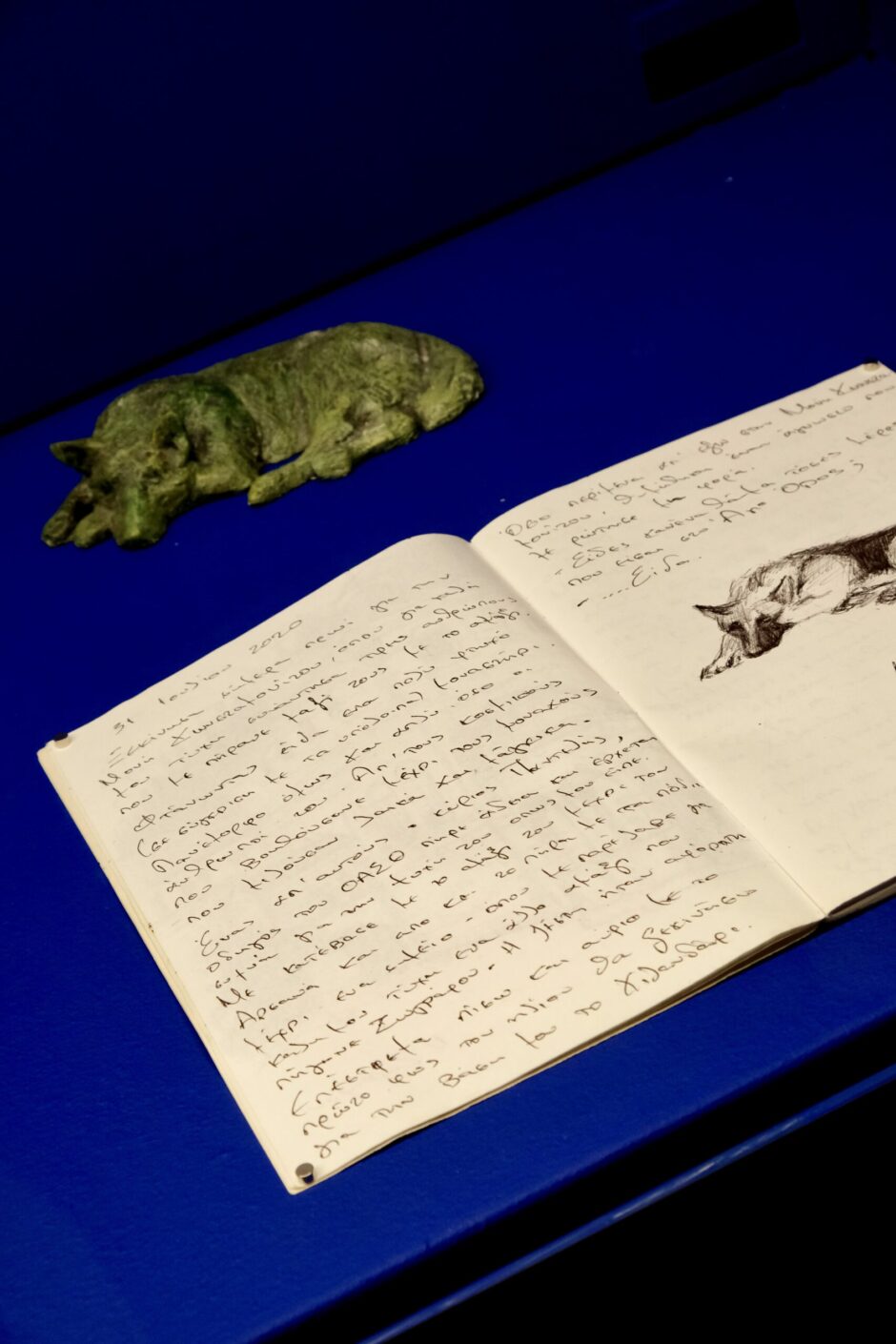

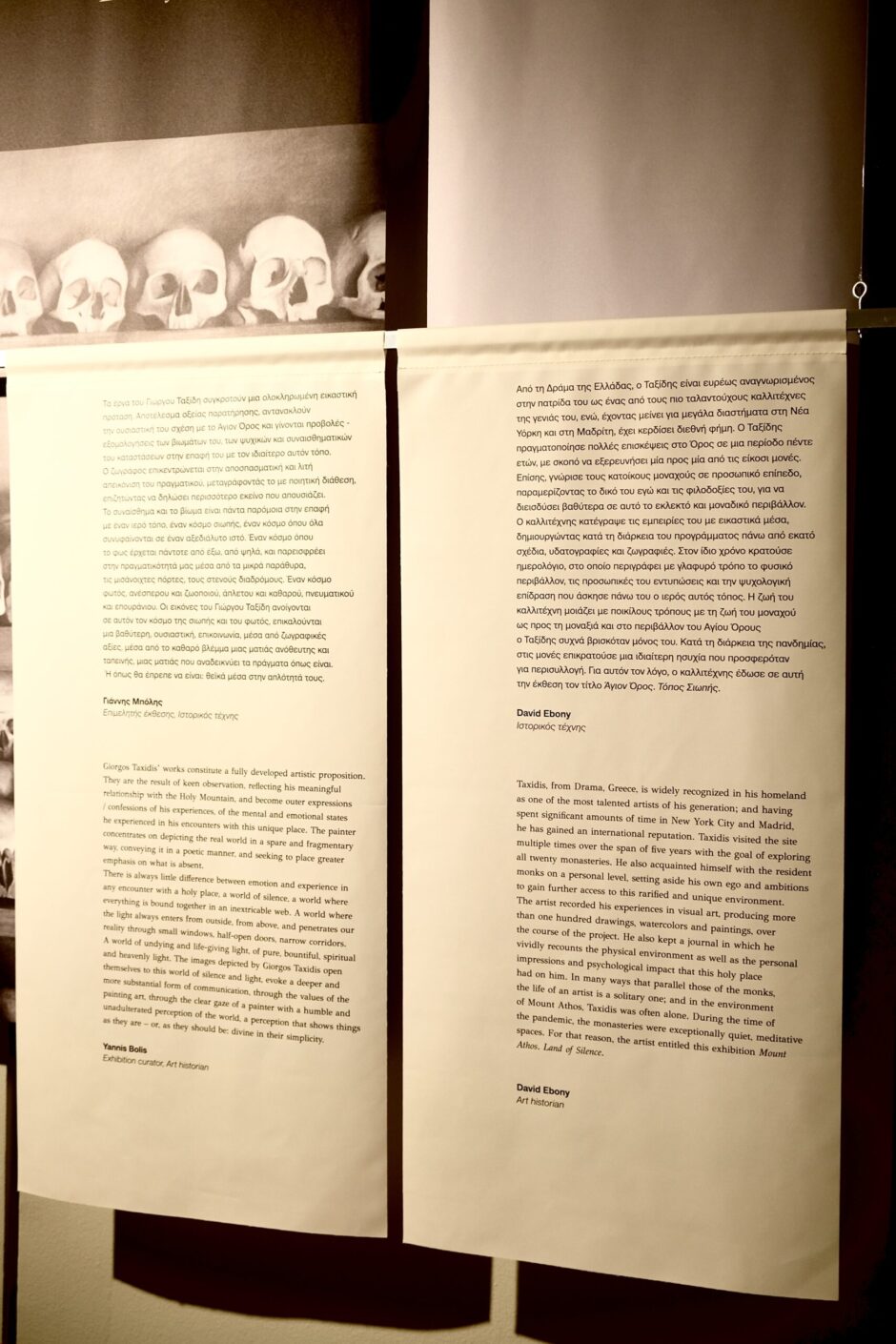

From 24 June 2025 to 11 October, the exhibition of paintings entitled ‘Giorgos Taxidis. Mount Athos: Land of Silence’ is opened in the exhibition space of the Mount Athos Center for visitors to enjoy. In the exhibition Mount Athos: Land of Silence, we can see 115 artworks of Giorgos Taxidis made throughout the period of five years (2020-2025) in various techniques such as pencil, charcoal, oil and watercolour, sculptures and prints and mixed media. Through his visits, he managed to observe and document the essence of Mount Athos and its peace and holiness. He kept a journal in which he documented his journey.

Giorgos Taxidis was born in 1987 and from 2010 to 2015 studied in the Department of Visual and Applied Arts in the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki’s School of Fine Arts, where he graduated with honours. Through the Erasmus programme (2013–2014), he studied at the School of Fine Arts of the University of Madrid (UCM, Facultad de Bellas Artes). Later (2017–2019), on a scholarship, he undertook postgraduate studies at the New York Academy of Art. He has received a total of 12 scholarships (from the Fulbright Foundation, the NEON Organization and the Georgios Varkas Legacy, among others). In 2012, he received a commendation from the Hellenic Post Office for a series of stamps entitled Europa 2012, and in 2014 won first prize in the Art and the City 5 competition in Athens. In 2018, his work was selected for the XL Catlin Art Prize competition, and in 2019 was awarded a prize by the Dahesh Museum of Art in New York. That year, he taught drawing at the San Domenico School of Fine Arts. He designed the Cyclops Award for the urban non-profit association Cyclops based in Drama. He has presented six solo exhibitions and has participated in numerous group shows in Greece and other countries. Works of his are to be found in private collections both in Greece and abroad.

In the following interview, he discusses the creative process behind the project and the insights he gained during his time on Mount Athos:

-Could you briefly describe your body of work? What is your biggest inspiration? Is there an artist or a culture you’re taking the most of?

Most of my works are figurative and center around the human being and the stories they carry. I mainly work with mediums such as pencil, charcoal, oil paint, watercolor, and pastels. I am also interested in more conceptual works, such as some installations I have created, but what concerns me most is painting. I greatly admire ancient Greek art for the issues of beauty it raised, the ideal of form, and its Doric essence. A number of artists from whom I draw inspiration are Rembrandt, Edward Hopper, Gerhard Richter, Andrew Wyeth, Anselm Kiefer, Käthe Kollwitz, and many others.

-What inspired you to create an exhibition on Mount Athos? What first drew you to Mount Athos as a subject? Was it the landscape, the spiritual tradition or something more personal?

I first received the proposal from Mr. Anastasios Douros, Director of the Mount Athos Center, while I was in New York. We talked about the project, and he provided me with plenty of material so I could get a clear idea of what I would be working on at Mount Athos. What really drew me in was the opportunity to engage with such a historic and deeply spiritual place, and the challenge of immersing myself in a world so different from my own.

-What was the most surprising thing you saw during your trips to Athos? What was your most magical experience there?

I was incredibly fortunate to gain access to places that are not easily open to visitors, such as the libraries of the monasteries, the museums, and the manuscript conservation rooms. It was truly unbelievable to be able to see up close imperial decrees, important texts, and manuscripts dating back to the 9th century. This experience is something I will never forget—just like the phone call I received one evening outside the Monastery of Saint Paul, when my wife told me she was pregnant.

David Ebony, former general manager of Art in America magazine and editor of leading art magazines in the USA, said that in many ways that parallel those of the monks, the life of an artist is a solitary one. How did living (even briefly) like a monk, not just as an artist, but within a completely different rhythm and sound of life- influence you?

I believe that an artist’s life isn’t so different from a monastic life. During the project, I worked almost nonstop, often in isolation. Of course, the rhythm at Mount Athos is completely different—it helps you reset your mind. It’s a kind of therapy. Nature plays a huge role, and being detached from phones and the internet allows you to reconnect with other important things we tend to overlook in our daily lives.

-Many describe Mount Athos as a place of “silence”. How did you translate that silence into visual language?

I believe that the absence of the human figure actually strengthened this impression. In all the works, there is no direct depiction of people—only traces of their presence, like a rumpled bed or a window lit at night. This creates a certain stillness, which we often associate with the absence of sound. The title of the exhibition came at the end for practical reasons; it wasn’t in my mind from the beginning. It emerged as an experience because that’s how I chose to see Mount Athos—silently.

-In this project, you’ve gathered many stories over time. While depicting the stories, you must have kept certain parts to yourself. What guided those selections and decisions?

The exhibition catalogue includes all the journals and notes I kept over those five years. But some things, we simply have to keep to ourselves. These are experiences that are hard to put into words. Sometimes, out of respect, these small stories are best left between those who shared them.

-Did this project change your personal understanding of spirituality, regardless of religion?

Absolutely, no one can remain unaffected, regardless of their religious background. It was five years filled with numerous trips, overnight stays, conversations, and walks through the forest, which gave me the time to process and reflect on the experiences I was gaining.

-What is the connection you see between art and religion? How do you think this experience has influenced your art?

For me, art is a search for truth, a way to reflect on myself and to turn my thoughts into a work. It demands focus and discipline. Religion shares these qualities—it can help elevate a person, lift them up, and connect them with something intangible, like God, if approached in the right way. An artist walks alone; it’s a solitary uphill journey. As Kandinsky once said, “The artist has undertaken the execution of a difficult task, which often becomes his Cross.”

-What is something that you took the most out of this experience? What was your biggest challenge during this project?

I painted subjects I had never tackled before—monk cells, the interiors of churches, natural landscapes, and more. It taught me technical skills, but also how to truly see a place. The biggest challenge was capturing it accurately, and I spent a lot of time exploring exactly what I wanted to paint. It was also a responsibility on my shoulders, since it was a commissioned work. Mount Athos has inspired hundreds of artists over the centuries, and I had to find a way to contribute my own interpretation.

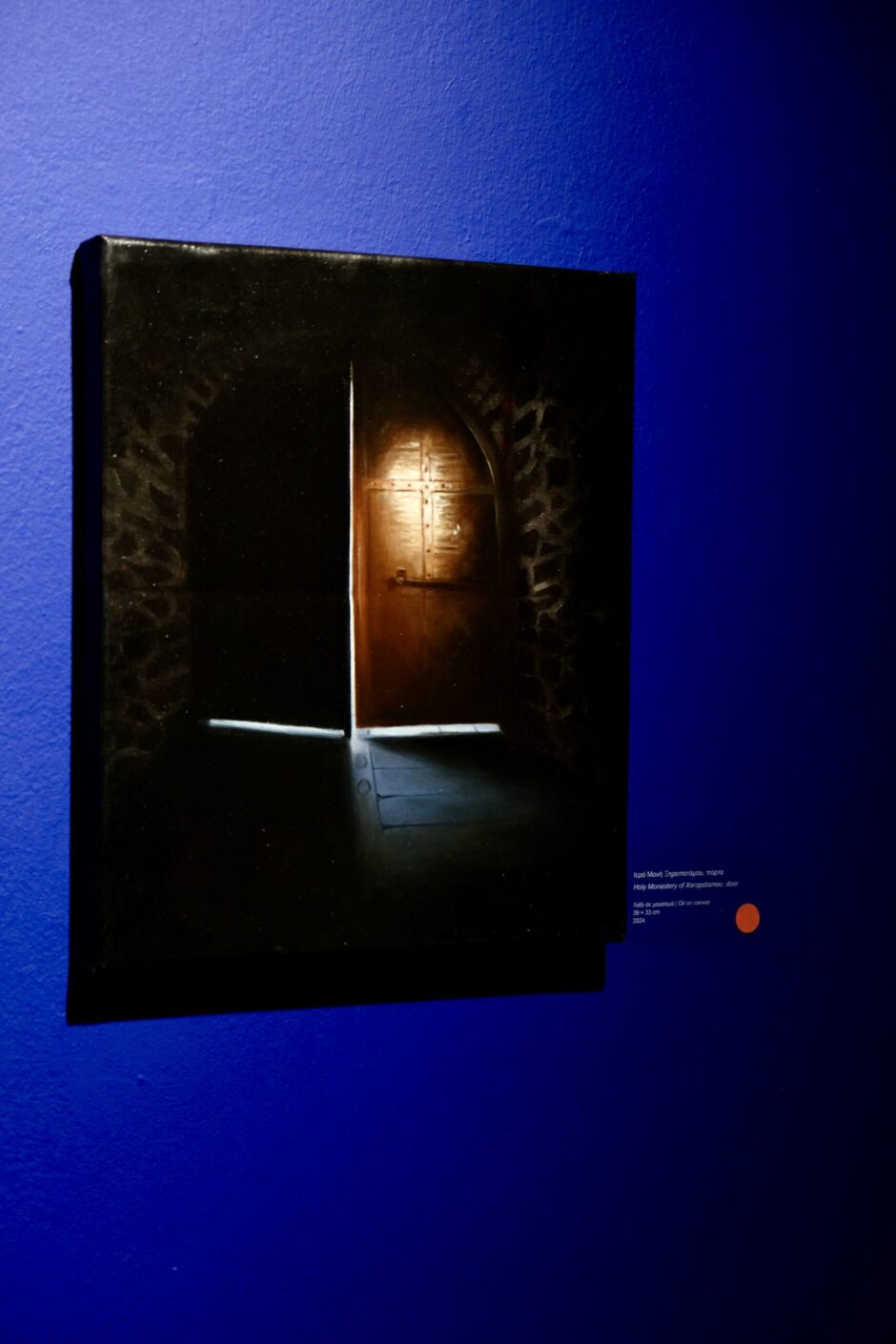

-What made you focus on the interior of the monastery? What did you want to say through the light in your artworks?

The exteriors of the monasteries can more or less be found with a simple online search. What interested me was the interior—both literally, like the cells I painted, and metaphorically. I decided to document all the rooms where I had slept. At first, this began as a simple record, an internal documentation of space—something that perhaps a viewer would never have the opportunity to see. Over time, however, it became a reflection of human presence in a place. In the early morning hours, after waking up to attend the liturgy, I would see my sheets and pillow bearing the imprint of my body. A person had been there—someone who had prayed, who had slept. It reminded me of the Holy Shroud. The interior of a space had transformed into the interior of a person. His absence allowed the viewer to become part of the experience, recalling their own personal moments at Mount Athos or engaging with it in a spiritual sense. Light always fascinated me because of the challenge it presents in capturing it. I realized that to make it truly dazzling, I had to leave the paper untouched and focus on what surrounds it—like truth, which cannot hide anything in its passage. The True Light.

-What are your next big projects after a large project such as Mount Athos?

For now, together with the Mount Athos Center, we are focusing on bringing the exhibition to other cities in Greece and abroad. It was such a major project, and I want to give it all the attention it deserves.

Basia Witkowska